Summary: Gas Prices 101

Ben Carlson has been talking about the dislocation between crude oil prices and gas prices for years. I think that he summed it up perfectly in this tweet:

It does feel like prices at the pump rise whenever crude oil is climbing but are much slower to fall when crude prices are retreating. Oil prices jumped about 40% when Russia invaded Ukraine to a high of over $130 a barrel. Gas prices quickly followed suit: in Winnipeg, Manitoba, gas rose from $1.49 to $1.73/litre between February 21 and March 9. They’ve stayed at that elevated level despite oil falling to $94.79 per barrel as of March 15.

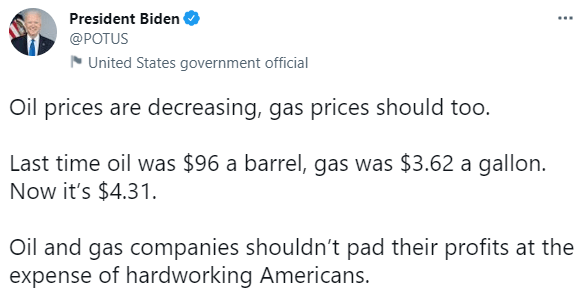

There is supposed to be an intrinsic tie between oil and gasoline. Even President Biden can’t wrap his head around the disconnect:

Why don’t gas prices move with oil prices in both directions?

Rockets and Feathers

The way in which gas prices move with crude prices has a name in the industry: rockets and feathers. When oil prices rise, gas shoots up like a rocket. When oil prices fall, gas drops like a feather.

This pricing practice is enabled by a phenomenon that’s fairly unique to gasoline: advertising prices on big signs along roadways. It’s an example of radical transparency that has been destructive for consumers. What’s the point of boldly advertising your price if everyone else charges the same amount? With the exception of some rebates offered at the pump, gas stations effectively do not compete based on price. Further, the product itself is a commodity that has to meet minimum quality standards to be sold for use in vehicles, and the “experience” provided by different gas stations is roughly the same. These are therefore businesses that aren’t competing on price, product, or consumer experience. This is a perfect recipe for cartel-like behaviour that ends up costing the end consumer. While price fixing is extremely difficult to prove indisputably, it clearly plays a role in this instance. The stations aren’t really signalling price to consumers, but rather to each other. Stations will raise prices immediately to reflect increased input costs, but they are hesitant to lower prices as there is no competitive pressure to do so until other stations do.

Economics 101

Gas is a commodity that represents a high degree of price inelasticity, meaning that people don’t tend to cut their consumption very much as prices rise. This doesn’t apply for products and services that are price elastic. If the price of carrots rises too high, for example, then I’ll start buying broccoli instead. We don’t see this with gas; there’s nothing else I can put in my car to make it go if I don’t want to pay for gasoline. Of course, this can eventually reach a tipping point. As petroleum products get more expensive, then alternative energy sources become more attractive not just from an emissions perspective, but also economically. One could argue that reduced gas use would be a silver lining to higher prices. However, pivoting a global economy that runs on oil and gas to renewables is a drawn-out process. In the short term, there is little economic pressure to induce price cuts for gas.

An old adage in economics states that the cure for high prices is high prices. Even a price inelastic good like gasoline will get to a point where households simply must reduce consumption due to budgetary constraints. Oil futures briefly went negative in April of 2020 when demand dried up because people were confined to their homes; falling prices resulted from reduced demand. You want gas prices to fall? Then drive less and lower the demand.

For more insightful articles on personal finance and money topics, click here.

Opinions are those of the author and may not reflect those of BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc., and are not intended to provide investment, tax, accounting or legal advice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness and neither the author nor BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. shall be liable for any errors, omissions or delays in content, or for any actions taken in reliance. BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bank of Montreal.