Introduction: Why Does Japan Have Such Low Interest Rates?

Most developed world countries stopped hiking interest rates by the summer of 2023. In Canada, the rate hike cycle came to an end in July after rates were raised by a cumulative 4.75% over a series of hikes starting in early 2022. The question being posed to most central banks these days is when rate cuts can commence, and that question was recently answered as the Bank of Canada cut its target overnight rate by 25 basis points (more info here).

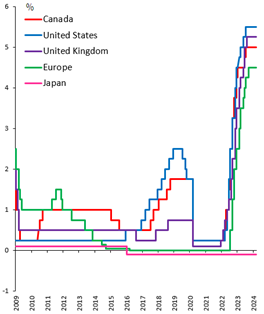

Japan bucked this trend in March 2024, when it announced a rate hike, its first in 17 years. Even after the hike, the target rate range for Japan’s central bank is just 0-0.1%. Contrast this with other developed economies:

So, the question is: why has Japan’s monetary policy been so different from its developed world peers such as Canada? To understand the present, we must study the past.

Historical Context of Japanese Economic Policies

Japan’s economy and stock market have followed an interesting trajectory over the last half-century. World War II left Japan’s cities destroyed and its industrial capacity gutted, and complete demilitarization was a condition of its surrender. Its economic recovery in the post-war years was nothing short of extraordinary: substantial policy and social reform spurred growth, and the destruction it suffered during the War was paradoxically beneficial, as the new factories that arose to replace those destroyed in the fighting were more efficient and equipped with the latest technology.

The 1980s belonged to Japan. Their stock market (the Nikkei) was positive every year between 1980 and 1989, and there was widespread belief Japan would dethrone the United States as the world’s foremost economic superpower. By the end of the decade, the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was estimated to be worth more than all the combined real estate in California.

Much of Japan’s market strength was justified: they had a productive workforce capitalizing on cutting edge technology, with innovative companies like Toyota and Sony to help lead the charge. The growth their stock market enjoyed was directionally appropriate, just at an unsustainable scale. Valuations became ridiculously stretched. Much of the growth was fuelled by debt secured by real estate, with loans that could be continuously refinanced so long as property values kept going up. Alas, trees don’t grow to the sky, and property values couldn’t go up forever. Defaults increased, liquidity dried up, and the Nikkei suffered declines of over 20% in 1991 and nearly 25% in 1992.

Demographics also had an impact. Japan’s population was aging and birth rates were slowing, contributing to a shrinking, less productive workforce. They also lacked a formal immigration policy (as of 2023, 97.5% of Japanese residents are ethnically Japanese), so there was little in the way of migration to help stimulate their economy.

March of 2024 was the first time the Nikkei reached an all-time high since December of 1989. You could have graduated, worked a long and meaningful career, and retired between all-time highs on the Nikkei.

The Double-Edged Sword of Japan’s Negative Interest Rates

Japanese politicians spent decades trying to fix the growth problem. Their central bank took aggressive action with interest rates, cutting rates into negative territory in 2016. Extremely low rates were intended to devalue the yen, which made Japanese exports more attractive to trade partners (just like Canadians see our buying power increase in the States when the loonie is strong relative to the US dollar). This was hard on Japanese households, however, as imports became more expensive. Japan’s attempts to strike the right balance in its currency manipulations are a bit like Homer trying to keep the lobster and the fish alive:

Lessons Learned Elsewhere and Future Prospects

Inflation has been a glaring problem over the past three years. Japan was faced with the flip side of this coin, deflation. While the causes are different, the net impact of an unstable price level, either due to deflation or excess inflation, is a drag on economic growth.

Aging populations similarly pose a challenge to modern developed economies. Economic growth is a function of a country’s population, the share of the population in the labour force, and improvements in productivity. The share of the population that has reached retirement age is growing every year and birth rates have fallen in the developed world, leading to declining labour force participation rates. Canada has revised and expanded its immigration policy in response to this current and projected labour shortfall (this has in turn ramped up the discourse surrounding Canada’s housing affordability issues). Complicated problems don’t have easy solutions).

Summary: Why does Japan have such low interest rates?

Euphoria and despair are emotional extremes best avoided in the realms of economics and investing. Japan experienced a meteoric rise and then faced the mother of all comedowns. The Japanese experience offers valuable lessons for modern policymakers, who hopefully can avoid learning these lessons the hard way.

Opinions are those of the author and may not reflect those of BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc., and are not intended to provide investment, tax, accounting or legal advice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness and neither the author nor BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. shall be liable for any errors, omissions or delays in content, or for any actions taken in reliance. BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bank of Montreal.