Summary: Differences Between Canadian & US Banks

Three banks in the US have failed this month. One of them, Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) was the 16th largest bank in the country. Problems at banks aren’t limited to this side of the Atlantic: UBS has stated its intent to purchase Credit Suisse in a government-backstopped transaction at a purchase price roughly 99% lower than Credit Suisse’s peak market value in 2007. As a Canadian, there’s likely no better time than the present to learn about the differences between Canadian & US banks.

It’s highly likely that there is more turmoil ahead. First Republic Bank stock is in freefall as it looks to raise funds through an emergency issue of new shares and there’s a good chance that it will be acquired in another fire sale.

I’m not going to use this article to make predictions on the fallout of these events, though I do have considerable faith in the system restabilizing. Rather, the focus of this piece is on the differences that exist between the Canadian and US banking systems, and why the events currently unfolding in the United States haven’t been an issue in Canada for most of our country’s history.

The differences between Canadian & US banks are a reflection of the differences between the demography, history, and political ideology of the two countries.

Demography

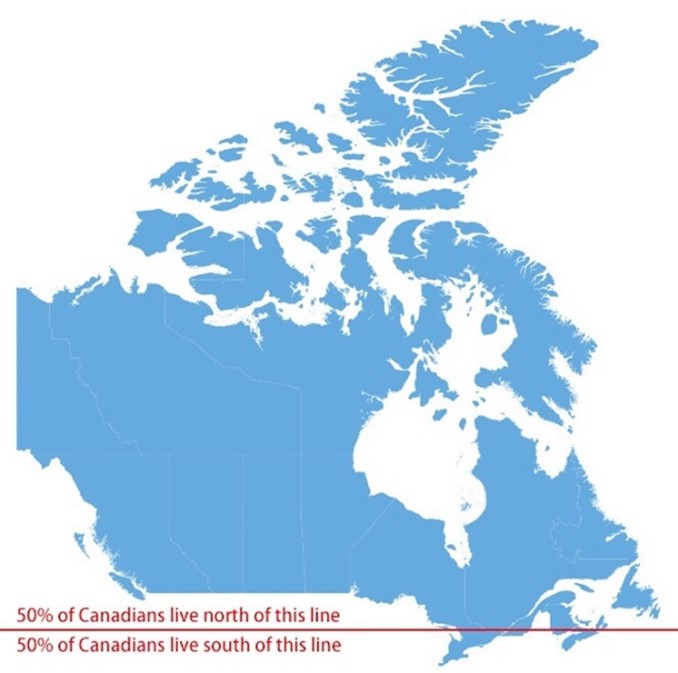

Canada is a very big country that is almost entirely empty. When visualized, the population distribution is staggering:

Our population is heavily concentrated, and our banking sector is too. The two largest companies in the TSX by market capitalization, and four of the top seven, are banks.

While the United States is geographically smaller, it is generally more fit to human habitation, which is a contributing factor to its population being roughly ten times greater than Canada’s. And these people are spread more evenly throughout the country. The American banking sector has been influenced by this, as regional and industry-specific banks are more feasible given this demography.

Regional and industry-specific banks can have single points of failure that you won’t see within larger, national banks. Take SVB, for example. It’s an institution that took great pride in a customer base operating on the cutting edge of technological progress. The companies that made up SVB’s client base were outsized beneficiaries of easy money as billions in venture capital funding sought out new opportunities in tech. Now that interest rates have risen so much and business conditions in general have become less favourable, many of these tech corporations have seen their fortunes turn. They could no longer rely on new equity raises or cheap debt funding and instead had to draw on their deposits with SVB. Some of the biggest names in tech, including Marc Andreessen and Peter Thiel, didn’t do SVB any favours when they turned to Twitter to broadcast their decision to pull deposits from the bank.

Canadian banks, by contrast, have more diverse and stable client bases, and are not as susceptible to single points of failure.

Politics & History in Banking

The respective banking sectors in the US and Canada are also a microcosm of differences in political ideology. The bias in Canada is focused on well-regulated banks operating nationally and being subject to a high degree of political scrutiny. The United States, on the other hand, adheres more firmly to the principle of division of power. Their national independence was won through a war fought over this very issue.

The political system in the US is based heavily on checks and balances, aimed at limiting power concentration. Policymakers and voters have extended this sentiment to the banking sector. Politicians on both sides of the aisle, from Maxine Waters to Donald Trump, have espoused the merits of supporting the country’s regional and community banks to avoid concentrating power in the hands of a few national banks.

This is to say nothing about the differences in regulations between Canada and the United States. While conditions for bank activity tightened in the States following the 2008 financial crisis, many of their banks don’t meet the liquidity metrics present in Canada. And the looser regulation is partially intended to support regional and community banks that would otherwise be unable to adhere to a heightened level of scrutiny.

The structures of the two countries’ banking sectors have led to vastly different outcomes. 565 US banks have failed since 2001; the last time a bank failed in Canada was 1923. Stability isn’t necessarily a reflection of a better system, but with all the uncertainties that exist in the world, I prefer having my deposits in a bank with a 200-year track record.

For more articles similar to this one (Canadian & US Banks Are Not The Same) by Max Kirouac, click here.

Opinions are those of the author and may not reflect those of BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc., and are not intended to provide investment, tax, accounting or legal advice. The information and opinions contained herein have been compiled from sources believed reliable but no representation or warranty, express or implied, is made as to their accuracy or completeness and neither the author nor BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. shall be liable for any errors, omissions or delays in content, or for any actions taken in reliance. BMO Private Investment Counsel Inc. is a wholly-owned subsidiary of Bank of Montreal.